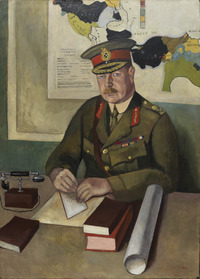

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

LINDSAY, WILLIAM BETHUNE, militia officer, engineer, civil servant, army officer, and businessman; b. 3 Nov. 1880 in Strathroy, Ont., son of William Baltimore Lindsay and Mary Jane Cameron; d. unmarried 27 June 1933 in Toronto and was buried in Strathroy.

W. B. Lindsay, whose parents were of English and Scottish descent, grew up in Strathroy, a small community in southwestern Ontario. His father was a physician and an early investor in several Canadian mining projects. W. B., also called Bill, began his education in 1890 at the Strathroy Collegiate Institute. Another pupil there was Arthur William Currie, the future commander of the Canadian Corps in the First World War, who was five years Lindsay’s senior. He later recalled that Bill was a “small, chubby boy.” In 1897 Lindsay went to Kingston’s Royal Military College of Canada, where he obtained a three-year degree in engineering. During his time there he played centre for the varsity football team and the Ottawa Rough Riders. In June 1900 he was commissioned a lieutenant in the Canadian militia, and the next month he took up an appointment as a draughtsman with the chief engineer’s branch of the federal Department of Marine and Fisheries, headed by Sir Louis Henry Davies*.

Following Canada’s involvement in the South African War, Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* and Minister of Militia and Defence Sir Frederick William Borden* significantly reformed and expanded the country’s military forces. The Royal Canadian Engineers (RCE) was created as a part of the Permanent Force, succeeding the Corps of Engineers, and Lindsay accepted a commission as one of the RCE’s five lieutenants. He resigned from the civil service in July 1904 and went to Kingston as chief engineer for Military District No.3 (eastern Ontario). On 1 July 1905 the Permanent Force assumed responsibility for manning British fortifications in Canada, and Lindsay was sent to Military District No.9 (Nova Scotia) to inspect the Halifax Citadel and oversee the transfer of authority. Promoted captain on 16 November, he would subsequently hold the position of district engineer in three military districts: No.2 (Toronto and central Ontario) from 1907 to 1910; No.11 (British Columbia and Yukon) from 1910 to 1912; and No.10 (a massive district encompassing Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and parts of the Northwest Territories and Ontario) from 1912 to 1914. He attained the rank of major on 1 May 1911.

After the First World War broke out in August 1914, Lindsay was given responsibility for training the first contingent of engineers at the military camp in Valcartier, Que. There he and his men accomplished the remarkable feat of constructing a 350-foot floating bridge across the Rivière Jacques-Cartier in four hours. Lindsay took command of the 2nd Field Company, Canadian Engineers, one of the three engineering companies assigned to the 1st Canadian Division. In England he oversaw the training of his 215 men, but he fell from his horse before their departure for the Western Front and the knee injury he suffered prevented him from rejoining them until 16 May 1915. At that time the company was in northern France, having just left Belgium’s Ypres (Ieper) salient, where Lindsay’s younger brother Arthur Lodge had been killed on 22 April.

Described by historian Tim Cook as a chain-smoker with a “Friar Tuck build – short in stature and wide in girth,” W. B. Lindsay proved himself to be a competent, efficient, and well-respected officer. “He had high expectations,” Cook notes, “but he afforded his subordinates full independence and they rarely failed him.” When the Canadian Corps was formed on 13 Sept. 1915 his friend Major-General Arthur Currie, who now led the 1st Canadian Division, helped persuade the corps’ commander, Lieutenant-General Edwin Alfred Hervey Alderson*, to appoint Lindsay as Currie’s divisional engineer. The post came with a promotion to lieutenant-colonel, effective retroactively from 1 July. After the corps’ chief engineer, Brigadier-General Charles Johnstone Armstrong, was injured in a 29 Feb. 1916 railway accident, Currie campaigned successfully for Lindsay to take his place. W. B., who assumed the post on 7 March and was promoted brigadier-general on 24 May, would remain chief engineer for the rest of the war.

On the Western Front, military engineers built and maintained roads, bridges, and waterworks, oversaw the construction and repair of field defences, tunnels, and mines, and protected signalling infrastructure – all work that was essential to fighting a trench war. As chief engineer, Lindsay oversaw what historian Bill Rawling describes as “a multi-purpose organization” that included the “technical elements of the army that did not fit logically elsewhere,” such as railway troops, supply wagons, and cartographers, as well as pioneer, tunnelling, and field companies. Lindsay’s approach to the battlefield was innovative: at Vimy Ridge, for example, where the Canadian Corps had its most famous victory in April 1917, his engineers dug tunnels or improved old French and British subways so that the infantry could be secretly deployed deep into no-man’s-land, avoiding the deadly shellfire above.

At the end of 1917 Lindsay proposed a major reorganization of the engineering component of the Canadian Corps, the purpose of which was to provide the engineers, who often had to rely on front-line infantry units for assistance, with direct command over specially assigned labour troops. Currie, who had succeeded Sir Julian Hedworth George Byng as commander of the corps in June, backed the plan because it would make the engineers more efficient and allow the infantry to focus on fighting. In their comments on the reorganization, historians Armine John Kerry and William Alexander McDill note that “when the days of trial came in August, the time and effort involved proved well justified.” During the Last Hundred Days campaign, from August to November 1918, Lindsay’s troops kept supplies and artillery support moving behind the rapidly advancing tanks and infantry. For example, at the Canal du Nord on 27 September, in an act reminiscent of their feat at Valcartier four years earlier, they quickly erected bridges to carry artillery pieces, tanks, and supply wagons across the unfinished canal. After the armistice Lindsay remained in command of the Canadian engineers, and after participating in the march to the Rhineland, he was stationed in England. When his staff returned home in June 1919, he volunteered to stay, working at the British War Office as a member of its commission on the reorganization of the Royal Engineers.

Lindsay retired from the military in December with the rank of major-general, travelled in Europe, and returned to Canada. In 1920 he secured a mineral lease to 1,920 acres of tar sands near Fort McMurray, Alta. Like his father, Lindsay had an interest in mineral exploration, and he hoped to develop a steam-based process that could extract the oil from the tar sands. He partnered with Professor Thomas George Madgwick of the University of Birmingham and the Anglo-Persian Oil Company to build an experimental plant near Swansea, Wales, close to Llandarcy, where the first oil refinery in Great Britain opened in 1922. That year Lindsay shipped a carload of Alberta tar sand to his new plant. Assisted by the federal Department of Mines, his company would ultimately send, at great expense, more than 40 tons of material overseas for testing and processing. In 1925, after years of inconclusive results, as well as difficulty in attracting capital investors and obtaining American patents, the company closed the plant and discontinued the project. Lindsay remained optimistic that commercialization was possible but told Charles Camsell, the deputy minister of mines, that “until oil can be produced from tar sands and sold in competition with oil derived from wells it does not appear to be feasible to develop these deposits economically.”

W. B. Lindsay remained active in the Canadian mining sector until his death from a heart attack at the Toronto Hunt Club on 27 June 1933, at the age of 52. His health had been poor for some time. Arthur Currie, writing to fellow wartime general Garnet Burk Hughes, expressed shock at his friend’s demise but observed that a few years earlier Lindsay had complained of “a rotten heart, high blood pressure, diseased kidneys, a bad tummy, bad knees and weak feet.” Currie recalled advising Lindsay to take care of himself and that he instead “went on a bender that lasted the best part of a week, after which he went to the hospital.” Reflecting on Lindsay’s talents and achievements, Currie concluded: “Bill had many excellent qualities, and I suppose his greatest contribution during the war was his plan for the re-organization of the Canadian Engineers, a decided factor in the efficiency of the Corps and one which had a lasting influence on the future organization of the engineers of the British division. No one can take from him the credit for that.”

The author would like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of John P. Sargeant of Strathroy, Ont., who graciously shared his own research, including rare newspaper clippings from the Age Dispatch (Strathroy).

FamilySearch, “Canada, Ontario births, 1869–1912,” William Bethems [sic] Lindsay, 3 Nov. 1880: www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FM8Y-THX?cid=fs_copy (consulted 17 July 2023). LAC, “Orders-in-Council,” no.1920-1547; RG9-III-C-5, vols.4394–400 (various administrative files related to Canadian engineers during WWI); RG9-III-D-3, vol.4988, file 635 (central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=fonandcol&id=2004859&lang=eng) and vol.4989, file 637 (central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=fonandcol&id=2005983&lang=eng) (War diaries – Chief Engineer – Canadian Corps, 1 May 1916–5 June 1919); vol.4990, file 640 (War diaries – 1st Brigade, Canadian Engineers, central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=fonandcol&id=2005984&lang=eng); vol.4994, file 652, pt.1 (War diaries – 2nd Battalion, Canadian Engineers, central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=fonandcol&id=2004872&lang=eng); RG13-A-2, vol.262, file 1921-1877 (Dept. of Interior – for draft lease to General Lindsay with tar sand rights); RG150, Acc. 1992–93/166, box 5657-25. Age Dispatch, 29 June 1933. Globe, 1 July 1933. Can., Dept. of Militia and Defence, Militia list (Ottawa), 1900–17; Dept. of the Secretary of State, The civil service list of Canada … (Ottawa), 1901; House of Commons, Debates, 1944, vol.3; Parl. Sessional papers, 1905, no.30. Canadian Engineer (Toronto), 24 Sept. 1914: 478. Tim Cook, Shock troops: Canadians fighting the Great War, 1917–1918 (Toronto, 2008). [Sir Arthur Currie], The selected papers of Sir Arthur Currie: diaries, letters, and report to the ministry, 1917–1933, ed. M. O. Humphries (Waterloo, 2008). Henderson’s British Columbia gazetteer and directory and mining companies, for 1899–1900 (Victoria and Vancouver), 1899. A. J. Kerry and W. A. McDill, The history of the Corps of Royal Canadian Engineers (2v., Ottawa, 1962–66), 1. J. L. Melville, “The Canadian engineers,” in Canada in the Great World War: an authentic account of the military history of Canada from the earliest days to the close of the war of the nations (6v., Toronto, 1917–21), 6: 37–74. Desmond Morton, A military history of Canada (5th ed., Toronto, 2007). G. W. L. Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914–1919: official history of the Canadian army in the First World War (Ottawa, 1962). Oil Trade Journal (New York), August 1922: 52. Bill Rawling, “The sappers of Vimy: specialized support for the assault of 9 April 1917,” in Vimy Ridge: a Canadian reassessment, ed. Geoffrey Hayes et al. (Waterloo, Ont., 2007). Western Ontario gazetteer and directory, 1898–99 (Ingersoll, Ont.), [1899?].

© 2024– University of Toronto/Université Laval

Image Gallery

Cite This Article

Mark Osborne Humphries, “LINDSAY, WILLIAM BETHUNE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed June 1, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lindsay_william_bethune_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lindsay_william_bethune_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Mark Osborne Humphries |

| Title of Article: | LINDSAY, WILLIAM BETHUNE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2024 |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | June 1, 2024 |